Did you always know that you wanted to study Space Physics?

In a nutshell, the answer is no. As a child, I was always fascinated by the night sky, planets, and space in general, and I felt an irresistible pull toward the unknown. I did not always know that I would study space physics, but I always knew that I wanted to push boundaries. For as long as I can remember, I have been captivated by the mysteries beyond our planet. My earliest dream was to become a rocket scientist and design propulsion systems that could break Earth’s boundaries and carry us to distant worlds. That passion led me to pursue Aerospace Engineering, where I immersed myself in propulsion at every opportunity, carefully shaping my academic path through electives and projects that aligned with my vision.

During a spacecraft propulsion course, I encountered plasma propulsion for the first time, including concepts such as ion thrusters and magnetohydrodynamic engines—methods of moving spacecraft using electrically charged gas rather than burning conventional fuel. The subject fascinated me, but it was only briefly covered, and no specialized course existed in my department. Determined to learn more, I sought guidance from senior students and eventually connected with a professor in Electrical Engineering who introduced me to plasma physics and Particle-in-Cell (PIC) simulations. PIC is a computer-based method in which particles such as electrons and ions—the building blocks of plasma—are treated as individual entities that move through electric and magnetic fields on a fixed background grid. This mentorship culminated in my B.Tech dissertation on grid generation for ion thruster studies, strengthening my resolve to pursue a PhD in space propulsion.

However, when I applied to U.S. universities, the professors I hoped to work with lacked funding that year, and I was unable to secure admission. During this period of uncertainty, I sought advice from Prof. Satya at IIT, whose perspective reshaped my trajectory. He cautioned against specializing too narrowly too early and encouraged me to build a strong foundation in a broader field before focusing on specific applications. Taking his advice, I shifted my focus to plasma physics and applied to programs that would allow me to explore its fundamentals.

This decision led me to pursue an M.S. in Applied Physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. My prior experience with PIC simulations helped me secure my first research project with Prof. Jan Egedal, where I studied magnetic reconnection. Magnetic reconnection is a dynamic process in which magnetic field lines break and reconnect, releasing energy that accelerates charged particles into space. A useful way to picture this process is to imagine a stretched rubber band snapping and suddenly releasing its stored energy. Magnetic reconnection is widespread throughout the universe—it occurs around the Sun and other stars, many planets, black holes, and even in distant galaxies and it is responsible for striking natural phenomena such as the Northern Lights. What makes this process particularly remarkable is that, although it occurs in regions only a few miles wide, its effects can extend across distances approaching a million miles, making it a key driver of space weather. Analyzing spacecraft data from the Cluster mission to study electron heating in near-Earth space, and later working on related projects, sparked a deeper passion for space physics than I had ever anticipated.

What began as a childhood dream to design rockets gradually evolved into a deep interest in plasma physics and magnetic reconnection. Today, I am motivated to study this phenomena not only to advance scientific knowledge, but also to help address the many unanswered questions about the space environment surrounding our planet.

What is your research focus?

Most of my research focuses on magnetic reconnection, and one of my projects examines how energy is converted during this process in the region where the solar wind enters Earth’s magnetic environment. Energy conversion is easiest to understand through familiar experiences, such as heating a balloon. When heat is added, the energy is neatly divided between warming the gas and causing the balloon to expand, following the first law of thermodynamics. This straightforward picture works well for systems that are in equilibrium, where energy is evenly distributed and the system is stable. However, most space plasmas are far from equilibrium and this simple picture fails. Until recently, research in this field relied on traditional methods of energy conversion that focus only on heating and expansion, leaving out a significant portion of the energy tied to irregular particle behavior. Recent work by Professor Paul Cassak and Hasan Barbhuiya provides a new way to calculate the energy associated with systems that are not in equilibrium. Using this theoretical framework, I apply advanced computer simulations to follow energy conversion at the level of individual particles during magnetic reconnection, helping us understand when and where energy is transferred, how particle irregularity and plasma waves play a role, and how solar wind energy ultimately enters Earth’s space environment.

For another project I’m working on identifying where magnetic reconnection is happening in large computer simulations using machine-learning techniques. Computer simulations are essential for understanding these complex systems and for helping interpret spacecraft measurements, but they also produce extremely large datasets that are difficult to analyze by hand. In simple simulations, reconnection is easy to track because the system is set up with two opposing magnetic fields forming a current sheet and when we perturb this current sheet reconnection occurs. However, in more realistic and complex computer simulations many thin current structures form naturally over time. Some of these structures undergo reconnection, while others do not, and they can vary widely in shape, size, and lifetime. This makes it much harder to determine where reconnection is taking place.

To address this challenge, we use machine-learning methods that can automatically find patterns in the data without prior labeling. In particular, we are using techniques like clustering to identify current sheets structures in the large scale simulations and use their geometric properties to distinguish which ones are most likely actively reconnecting. This approach allows us to systematically determine where and when magnetic reconnection occurs in complex, dynamic simulations providing new tools for studying space plasmas in simulations that closely resemble real space conditions.

What skills are most useful to you in your work, and where did you develop those skills?

Much of my work involves using computers to solve the equations that we think describe nature and analyze data from spacecraft. For simple analysis and observations, Python and IDL have been particularly powerful tools. For observational studies, I primarily use SPEDAS/PYSPEDAS. Particle-in-cell (PIC) codes are typically written in C/FORTRAN and while it is not always necessary to understand every detail of the code, having a strong background in C/C++ allows me to dive deeper when needed—whether to understand how routines and functions are structured and called, how the code executes, or where modifications can be made, such as changing a setup or adding new diagnostics.

In addition, a solid working knowledge of MATLAB and high-performance computing is essential for conducting this research effectively. I believe it is not necessary to know every programming language at the outset of your career; once you have a strong foundation in any programming language or tool, picking up new languages becomes much easier. For example, when I started my postdoctoral work, I had no prior experience with IDL, but I was able to learn it quickly because of my background in MATLAB, C, and Python.

Beyond coding, strong analytical skills in mathematics and physics are equally important and often prove invaluable in addressing complex research problems.

The true beauty of science: it is not a destination, but a horizon which is always receding, always beckoning, urging us to chase it with curiosity and courage.

What is an interesting problem or hurdle that you’ve overcome in your work?

In 2023, my mentor, Li-Jen Chen, was investigating Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission (MMS) spacecraft observations from an April 2023 CME event. During one of our meetings, she pointed out that the data did not follow the familiar pattern of solar wind flowing through the magnetosheath into Earth’s magnetosphere. She encouraged us to take on the challenge, and each member of our team stepped in to tackle a different piece of the puzzle.

I focused on analyzing electron distributions from the Fast Plasma Investigation (FPI) instrument aboard the MMS spacecraft, while other team members examined current structures, boundary layers, and ran global simulations of the storm conditions to understand how the magnetosphere had been transformed. Throughout this process, we were guided by our mentor, Li-Jen Chen. Through careful and extensive analysis, we worked through the data step by step, and gradually, the picture began to emerge. What we discovered was both fascinating and rare for Earth. Under normal conditions, Earth’s bow shock forms when the supersonic solar wind encounters the magnetosphere and slows down. However, during the 2023 CME event, the solar wind density dropped so low that a bow shock could not form. As a result, Earth’s magnetosphere adopted a new configuration in which the magnetotail split into two distinct structures—the dawn and dusk Alfvén wings. Such configurations are extremely rare at Earth but are commonly observed in the magnetospheres of bodies like Ganymede, one of Jupiter’s moons, and are also thought to occur around other planetary systems. Working on this project was an incredibly fulfilling and empowering experience, made even more meaningful by the strong sense of teamwork.But science isn’t just about breakthroughs; it's about resilience. One of my toughest hurdles came with my first paper. The peer-review process tested me in ways I didn’t expect. Convincing reviewers that your results matter, addressing every comment without losing focus, was exhausting. At times, I questioned myself: Am I a good scientist? Is my analysis sound? My mentor’s advice changed everything: “You don’t have to answer every question. Leave space for others to explore, and that’s how science grows.”

Those experiences taught me something profound: research is not a straight path. It’s a winding trail of uncertainty, collaboration, and growth. Every obstacle, whether an intensive dataset or a critical review, is an invitation to learn, adapt, and push the boundaries of what we know. And that, to me, is the true beauty of science: it is not a destination, but a horizon which is always receding, always beckoning, urging us to chase it with curiosity and courage.

What is one of your favorite moments in your career so far?

One of my most memorable moments was the day I received award from the Physics Department for conducting good research and for my overall performance that year. The award included $3,000 to support my travel and graduate studies, which meant a great deal to me both professionally and personally.

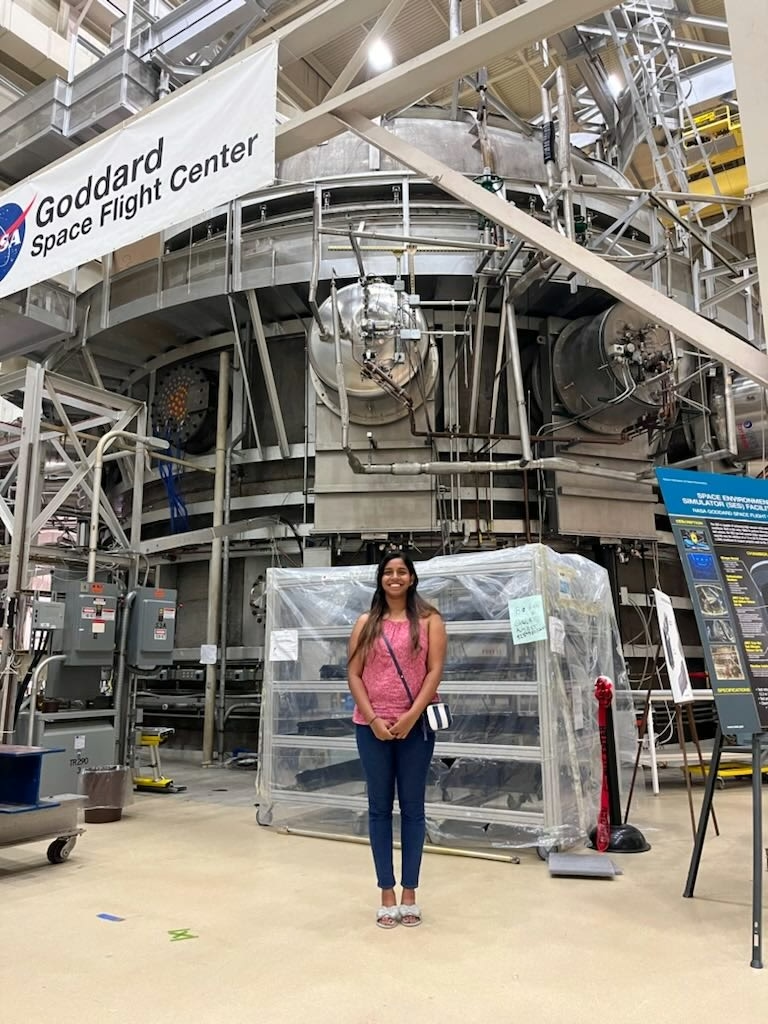

Another favorite moment was coming to NASA Goddard Space Flight Center for my postdoctoral position. In hindsight, it felt especially meaningful because, as an undergraduate and in my younger years, I had dreamed of being a rocket scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Joining NASA GSFC became a true “pinch-me” moment—one that reminded me how far I had come and why I pursued this path in the first place.

Where do you see yourself in the near future?

While I am eager to continue working at NASA as a scientist in space plasma physics, I am also exploring opportunities beyond NASA Goddard. I am currently at crossroads in my career, deciding whether to pursue an academic path toward becoming a university professor in space physics or to transition into Fusion Industry. In industry, I am particularly interested in roles where I can apply my expertise in plasma simulations and code development, especially in the field of plasma fusion. I am actively exploring opportunities and applying in both sectors, but regardless of the path I choose, I see myself continuing to work in the field of computational plasma physics.

What do you like to do in your free time?

In my free time, I enjoy solving puzzles—especially variant Sudoku. My current favorite is fog-of-war Sudoku, where the grid is initially hidden, and each correct entry gradually reveals more of the puzzle. These puzzles are entirely logic-based, with no guessing involved, which makes them both deeply satisfying and delightfully challenging. I often find myself absorbed in them for hours at a time.

I regularly participate in the monthly Sudoku Hunt hosted by Cracking the Cryptic, where themed puzzles turn problem-solving into a friendly and engaging competition. When I am not solving puzzles myself, I enjoy watching YouTube videos to learn new techniques and approaches, particularly from channels such as Numberphile. I have also recently started following 3Blue1Brown, which focuses on teaching higher mathematics through intuitive and visually driven explanations. The animations on the channel are created using a Python based code animation tool called Manim, and I have begun exploring tutorials to learn how to create similar visualizations myself, with the goal of communicating physics concepts more clearly and creatively.

Beyond puzzles, I’ve been taking pottery classes. There’s something humbling about shaping clay with your hands—the quiet rhythm of it, and the way imperfections slowly become character. Cooking brings me a similar joy, with the added warmth of nourishing others. After moving here, I began hosting Diwali dinners, and those evenings—filled with laughter, aromas, and shared stories—are among my happiest memories.

Nature is my reset button. A walk along the Paint Branch Trail can dissolve the weight of any day. And then there’s food exploration with friends—we’ve been tasting our way through Asian cuisines across the city. For me, free time isn’t about escape, but about discovery. Whether it’s a puzzle, a pot, a plate, or a path through the woods, I’m always drawn to whatever invites curiosity, craft, and connection.

Published Date: Jan 30, 2026.

Hometown:

Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Undergraduate Degree:

B.Tech (Hons) in Aerospace Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, India

Post-graduate Degrees:

M.S. in Electrical Engineering -Applied Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USAPhD. In Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA